Provincial and Territorial Energy Profiles – Northwest Territories

On this page:

Connect/Contact Us

Please send comments, questions, or suggestions to

energy-energie@cer-rec.gc.ca

-

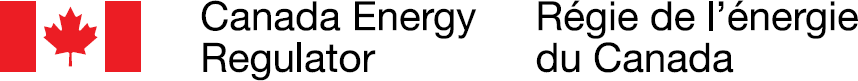

Figure 1: Hydrocarbon Production

Source and Description:

Source:

CER – Estimated Production of Canadian Crude Oil and Equivalent and Marketable Natural Gas Production in CanadaDescription:

This graph shows hydrocarbon production in NWT from 2013 to 2023. Over this period, crude oil production has decreased from 11.3 Mb/d to 4.0 Mb/d. Natural gas production has deceased from 12.1 MMcf/d to 4.9 MMcf/d. -

Figure 2: Electricity Generation by Fuel Type (2021)

Source and Description:

Source:

CER – Canada's Energy Future 2023 Data Appendix for Electricity GenerationDescription:

This pie chart shows electricity generation by source in NWT. A total of 0.71 TWh of electricity was generated in 2021. -

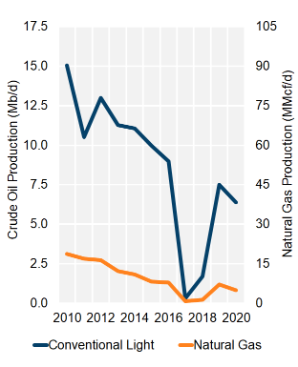

Figure 3: Crude Oil Infrastructure Map

Source and Description:

Source:

CERDescription:

This map shows major CER-regulated crude oil pipelines in NWT.Download:

PDF version [665 KB] -

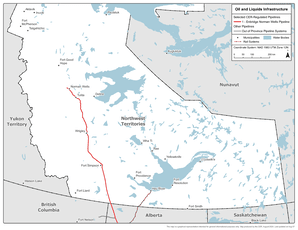

Figure 4: Natural Gas Infrastructure Map

Source and Description:

Source:

CERDescription:

This map shows CER-regulated natural gas pipelines in NWT.Download:

PDF version [698 KB] -

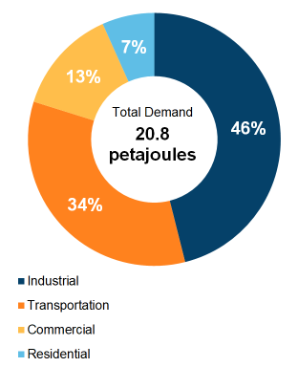

Figure 5: End-Use Demand by Sector (2020)

Source and Description:

Source:

CER – Canada's Energy Future 2023 Data Appendix for End-Use DemandDescription:

This pie chart shows end-use energy demand in NWT by sector. Total end-use energy demand was 17.5 PJ in 2020. The largest sector was industrial at 46% of total demand, followed by transportation (at 33%), commercial (at 14%), and lastly, residential (at 7%). -

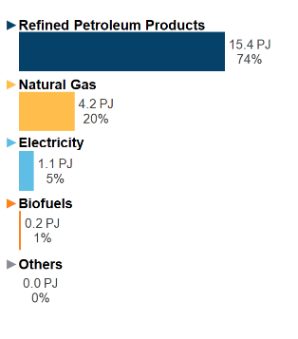

Figure 6: End-Use Demand by Fuel (2020)

-

Source and Description:

Source:

CER – Canada's Energy Future 2023 Data Appendix for End-Use DemandDescription:

This figure shows end-use demand by fuel type in NWT in 2020. Refined petroleum products accounted for 13.2 PJ (76%) of demand, followed by natural gas at 3.1 PJ (18%), electricity at 1.1 PJ (6%), biofuels at 0.1 PJ (1%), and other at 0.0 PJ.

Note: "Other" includes coal, coke, and coke oven gas. -

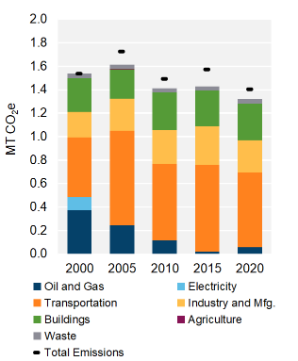

Figure 7: GHG Emissions by Sector

Source and Description:

Source:

Environment and Climate Change Canada – National Inventory Report 1990-2022Description:

This stacked column graph shows GHG emissions in NWT by sector from 2005 to 2022 in MT of CO2e. Total GHG emissions have decreased in NWT from 1.73 MT of CO2e in 2005 to 1.35 MT of CO2e in 2022. -

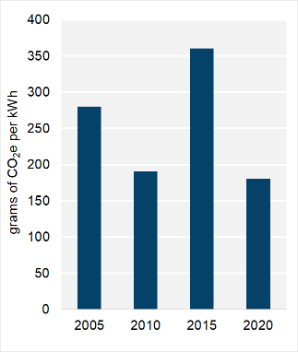

Figure 8: Emissions Intensity from Electricity Generation

Source and Description:

Source:

Environment and Climate Change Canada – National Inventory Report 1990-2022Description:

This column graph shows the emissions intensity of electricity generation in NWT from 2005 to 2022. In 2005, electricity generated in NWT emitted 280 g of CO2e per kWh. By 2022, emissions intensity decreased to 180 g of CO2e per kWh.

Energy Production

Crude Oil

- In 2023, Northwest Territories (NWT) produced 4.0 thousand barrels per day (Mb/d) of light crude oil (Figure 1). All production is from the Norman Wells Proven Area near the town of Norman Wells in the central Mackenzie Valley.

- NWT accounts for less than 0.1% of total Canadian crude oil production.

- NWT’s crude oil resources are estimated at 1.2 billion barrels.Footnote 1

- Several exploratory wells were drilled for shale gas and shale oil exploration in the Central Mackenzie Valley from 2012 to 2015. There has been no activity since 2015. In addition, no wells are currently planned or operating in other parts of NWT, including the federal waters of the Beaufort Sea.

- In December 2016, the federal government announced that Canadian Arctic offshore, including the federal waters offshore of Nunavut, is indefinitely off limits to new offshore oil and gas licensing, to be reviewed every five years through a climate and marine science-based life-cycle assessment.

- In 2019, the federal government issued an order, expiring at the end of 2021, prohibiting all oil and gas activities in the Canadian Arctic offshore, including activities associated with existing licenses.Footnote 2 This order was most recently amended on 8 December 2023 to extend the expiry date to 31 December 2028.Footnote 3

- In 2023, the “Report of the Western Arctic Review Committee” was issued.Footnote 4 This report was a science-based assessment of the risks and benefits of Arctic offshore oil and gas exploration and development.

- In 2023, the Government of Northwest Territories signed the Western Arctic – Tariuq (Offshore) Accord along with the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation, Government of Yukon, and Government of Canada.Footnote 5 This accord ensures that northerners will share in the co-management of offshore oil and gas activity.

Refined Petroleum Products (RPPs)

- There are no refineries in NWT.

Natural Gas/Natural Gas Liquids (NGLs)

- In 2023, natural gas production in NWT was 4.9 million cubic feet per day (MMcf/d) (Figure 1). This represented less than 0.1% of total Canadian natural gas production.

- Natural gas is produced in two fields in NWT: Norman Wells and Ikhil, with Norman Wells accounting for most of the production.Footnote 6 Natural gas has historically been produced at Cameron Hills in southern NWT, but production was suspended in 2015 for economic reasons.

- Natural gas production from Imperial’s Norman Wells is a byproduct of oil production, and the gas is used to generate electricity for the town of Norman Wells.Footnote 7 Norman Wells began producing in the 1920s.

- Natural gas production from Ikhil began in 1999 to supply the town of Inuvik for space heating and power generation. Currently, the Ikhil field is in decline and is now a secondary source of natural gas supply for Inuvik who now rely on propane and LNG delivered from the southern provinces.Footnote 8 In 2023, Ikhil produced 0.6 MMcf/d of natural gas. Prior to delivered LNG in 2013, Ikhil produced an average 1.5 MMcf/d.Footnote 9

- The decline in gas production at Ikhil was a major driver behind the Inuvialuit Energy Security ProjectFootnote 10 (IESP). The IESP is proposed to provide a secure source of energy for the town of Inuvik and the hamlet of Tuktoyaktuk from natural gas extraction from the TUK M-18 well in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region. The project also includes the construction of a plant to convert the natural gas into compressed natural gas and synthetic diesel for power and heating. The project would reduce the need for LNG and diesel delivered from southern provinces. The CER’s Commission approved the IESP in March 2024.Footnote 11

- Southern NWT is estimated to have 48 trillion cubic feet of recoverable, sales-quality natural gas resources, mostly shale gas in the Liard Basin.Footnote 12

- There is currently no NGL production in NWT.

Electricity

- In 2021, NWT generated about 0.71 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity (Figure 2), which is approximately 0.1% of total Canadian production. This includes electricity generated by communities and at industrial sites. NWT has an estimated generating capacity of 233 megawatts (MW).

- In 2021, 47% of NWT’s electricity came from petroleum and 36% came from hydroelectricity.

- NWT does not have a territorial electricity grid, however, eight communities around the Great Slave Lake use hydroelectricity serviced by two regional grids. Of the remaining 25 communities in NWT, 23 rely on diesel-fired power plants. Norman Wells uses natural gas for electricity generation and Inuvik has both diesel and natural gas facilities.Footnote 13

- The Northwest Territories Power Corporation (NTPC) generates NWT’s electricity from hydro, fossil fuel, and renewable sources. The major hydro generators include the Snare (30 MW), Bluefish (6.6 MW), and Taltson (18 MW) hydro systems.

- The Government of NWT is working on the Taltson Hydroelectric Expansion Project with the goal of expanding the capacity of the existing Taltson generating station and connecting the Taltson and Snare hydroelectric systems to improve overall reliability.Footnote 14 The expansion would add 60 MW of capacity.

- Naka Power (formerly Northland Utilities Ltd.Footnote 15) operates diesel generators to provide power to Dory Point-Kakisa, Fort Providence, Sambaa K’e, and Wekweeti.

- The Inuvik natural gas-fired power plant, which was supplied by the Ikhil gas field from 1999 to 2012, was restarted in January 2014 with LNG imported by truck from Alberta and British Columbia (B.C.). In December 2021, NTPC was approved for a grant to install a third LNG tank at the Inuvik power plant that will allow the community to rely less on its diesel generator for electricity.Footnote 16 NTPC is also evaluating the potential to supply other NWT communities on the road system with LNG to fuel local generators along with diesel.

- Wind energy provides approximately 4% of NWT’s electricity capacity. In 2012, the Diavik Diamond Mine installed four wind turbines with a capacity of 9.2 MW to provide electricity for its primarily diesel-based microgrid at Lac de Gras.Footnote 17

- Diavik is also planning to install northern Canada’s largest solar farm. The solar array is expected to provide up to 25% of Diavik’s electricity for operations and for closure work that will run until 2029. Commercial production from the Diavik mine is expected to end in early 2026.Footnote 18

- The 3.5 MW Inuvik High Point Wind Project was operational in fall 2023. The project included a new transformer and battery storage system. The project is expected to contribute to the NWT’s 25% diesel reduction target for electricity.Footnote 19

- While solar generated less than 1% of NWT’s electricity needs in 2021, many communities have installed small-scale and utility-scale solar capacity. Some noteworthy installed projects include:

- A 100 kW solar array in Fort Simpson, the largest solar system in northern Canada at the time, was installed in 2012.

- Colville Lake has been powered by a solar/battery and diesel hybrid system since 2016. The settlement, located north of the Arctic Circle, previously relied entirely on diesel-fired generation.Footnote 20

- New solar power facilities were installed in Fort Liard (10 kW) and Wrigley (60 kW) in 2016 and in Aklavik (55 kW) in 2017.

- A 165 kW ground-mounted plant adjacent to the North Mart store in Inuvik.

- A 1 MW solar farm in Inuvik on a former industrial site.Footnote 21

- NWT’s Net Metering ProgramFootnote 22 allows electricity customers to generate their own electricity (up to 15 kW) from renewable energy sources and accumulate energy credits monthly for any excess energy they produce, to be used against those months when their usage exceeds their production.

- The Government of NWT’s 2030 Energy StrategyFootnote 23 is being implemented along with the Climate Change Strategic Framework (CCSF) and the NWT carbon tax. One of the strategic objectives of the 2030 Energy Strategy is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from electricity generation in diesel-reliant communities by 25%.

Energy Transportation and Trade

Crude Oil and Liquids

- The Norman Wells Pipeline transports crude oil production from NWT and northwest Alberta to Zama, Alberta, where it connects with the Alberta oil pipeline network (Figure 3). This CER-regulated pipeline has a current capacity of about 16 Mb/d but only transported an average of 5.0 Mb/d in 2023.Footnote 24

- There are no crude-by-rail facilities in NWT. However, a rail terminal at Hay River receives RPPs, such as gasoline and diesel, from Alberta. These RPPs are delivered to communities in NWT and Nunavut via barges that travel along Great Slave Lake, the Mackenzie River, and the Beaufort Sea.

Natural Gas

- Much of Inuvik’s population is reliant on natural gas and Inuvik Gas Ltd.Footnote 25 is the operator of Inuvik’s local distribution system. Inuvik Gas Ltd. is regulated by the NWT Public Utilities Board.Footnote 26

- A 50 km pipeline connects Ikhil gas field to the town of Inuvik (Figure 4). The pipeline is jointly regulated by the CER and the Office of the Regulator of Oil and Gas Operations (OROGO)Footnote 27 under the Northwest Territories' Oil and Gas Operations Act.Footnote 28

- The Mackenzie Gas ProjectFootnote 29 was cancelled in December 2017 by project participants Imperial Oil, ConocoPhillips Canada, ExxonMobil Canada, and the Aboriginal Pipeline Group.Footnote 30 The proposed project involved the development of three natural gas fields in the Mackenzie Delta and the construction of a 1,220 km gas pipeline (the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline) that would extend from the Mackenzie Delta to Alberta’s NGTL gas transmission system. The project was considered not economically feasible.Footnote 31

Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG)

- Inuvik receives LNG via truck from several suppliers in Alberta and British Columbia. This LNG is used by NTPC’s Inuvik LNG facility, which began operation in 2013 and was constructed to store and re-gasify LNG for use in the Inuvik gas-fired power plant, reducing the need for electricity produced by diesel generators.Footnote 32

Electricity

- NTPC distributes electricity to end-use customers in 26 of the 33 communities across 565 km of transmission lines and 375 km of distribution lines.Footnote 33

- Naka Power also distributes electricity to Yellowknife, N’Dilo, Hay River, Sambaa K’e, Kakisa, Dory Point, Fort Providence, Wekweeti, Enterprise, and K’at’lodeeche.

- Both NTPC and Naka Power are regulated by the NWT Public Utilities Board.Footnote 34

- Because of long distances from populated areas to neighbouring provinces and territories, there are no transmission lines to enable the trade of electricity between NWT and other jurisdictions.

- There are two regional electricity grids in NWT: the North Slave (Snare Grid) and South Slave (Taltson Grid) regions. Both grids are connected to NWT’s hydroelectric supply, but do not connect with each other. Additionally, there are 25 local, independent systems not connected to either regional grid. The Taltson Hydro Expansion Project aims to integrate NWTs’ hydro capacity into one hydro grid.Footnote 35

- The first phase of the proposed Taltson Hydro Expansion consists of connecting the Snare and Taltson grids. A later phase involves the integration of NWT’s electrical grid with Alberta or Saskatchewan.Footnote 36

Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions

Total Energy Consumption

- End-use demand in NWT was 17.5 petajoules (PJ) in 2020. The largest sector for energy demand was industrial at 45% of total demand, followed by transportation at 33%, commercial at 14%, and residential at 7% (Figure 5). NWT’s total end-use energy demand was the third smallest in Canada, and the third largest on a per capita basis.

- RPPs were the largest fuel type consumed in NWT, accounting for 13.2 PJ, or 76% of total end-use demand. Natural gas and electricity accounted for 3.1 PJ (18%) and 1.1 PJ (6%), respectively (Figure 6).

Refined Petroleum Products

- NWT’s motor gasoline demand in 2022 was 1,022 litres per capita, 1% below the national average of 1,035 litres per capita.

- NWT’s diesel demand in 2022 was 4,740 litres per capita, more than six times the national average of 772 litres per capita.

- Virtually all the gasoline consumed in NWT is produced in neighbouring provinces (primarily Alberta) and transported to NWT by truck, rail (to Hay River), and barge.

- A significant portion of NWT’s demand for diesel fuel is for space heating and power generation. Diesel-based power plants accounted for 68% of NWT’s total installed power capacity in 2021.

- NWT’s sparse population and limited transportation infrastructure limits the supply and increases the cost of heating and transportation fuels. The territorial government’s Fuel Services Division oversees the purchase, transport, distribution, and storage of fuels for 16 communities not served by private companies. Fuel Services also manages the purchase, transport, and storage of diesel for NTPC power plants in 20 communities on behalf of the NTPC.Footnote 37

Natural Gas

- In 2023, NWT consumed an average of 4.8 MMcf/d of natural gas, which represented less than 0.1% of total Canadian demand.

Electricity

- In 2020, annual electricity consumption per capita in NWT was 6.6 megawatt-hours (MWh). NWT ranked second last for per capita electricity consumption and consumed 55% less than the national average.

- NWT’s largest consuming sector for electricity in 2020 was commercial at 0.18 TWh. The residential and industrial sectors consumed 0.11 TWh and 0.01 TWh, respectively.

- Because of its low population density and expensive generation costs, NWT has some of the highest electricity prices in the country. Prices in many communities exceed 30 cents per kWh for the first 600 kWh, although prices vary across communities and utility companies.Footnote 38

GHG Emissions

- NWT’s GHG emissions in 2022 were 1.35 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MT CO2e).Footnote 39 NWT’s GHG emissions have decreased 12% since 2000, the first full year after part of NWT became Nunavut. Emissions have decreased 22% since 2005.

- NWT’s emissions per capita are the highest in the northern territories at 30.3 tonnes CO2e, which is 67% above the Canadian average of 18.2 tonnes per capita.

- The largest emitting sectors in NWT are transportation at 46% of emissions, industries and manufacturing (excluding construction) at 28%, and buildings at 10% (Figure 7).

- NWT’s GHG emissions from the oil and gas sector in 2022 were 0.07 MT CO2e, attributable to crude oil and natural gas production.

- In 2022, NWT’s power sector emitted 58,000 tonnes of CO2e, which represents about 0.1% of Canadian emissions from power generation.

- The greenhouse gas intensity of NWT’s electricity grid, measured as the GHGs emitted in the generation of the territory’s electric power, was 180 grams of CO2e per kilowatt-hour (g CO2e/kWh) in 2022. This is a 36% reduction from the territory’s 2005 level of 280 g CO2e/kWh. The national average in 2022 was 100 g CO2e/kWh (Figure 8).

Energy Authorities

- Northwest Territories Bureau of Statistics: Oil and Gas Production

- Government of Northwest Territories: 2022-2023 Energy Initiatives Report

- Government of Northwest Territories: Industry, Tourism and Investment

- Government of Northwest Territories: Retail Fuel Prices

- Northwest Territories Public Utilities Board

- Northwest Territories Power Corporation: Current Alternative Energy Projects

- CER–Canada's Renewable Power: Northwest Territories

- Date modified: