ARCHIVED – Nuclear Generation in Canada

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

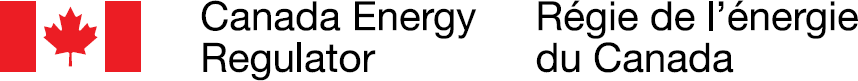

Nuclear power plants have been producing commercial electricity in Canada since the early 1960s. Four active nuclear power plants are in operation in Canada, with 19 operating nuclear reactors (Figure 4). Three plants are located in Ontario and one in New Brunswick. Quebec is the only other province to have used nuclear generation. In December 2012, Quebec’s Gentilly-2 nuclear generating facility was permanently shutdown.

Figure 4: Canada’s nuclear facilities

Source: NEB

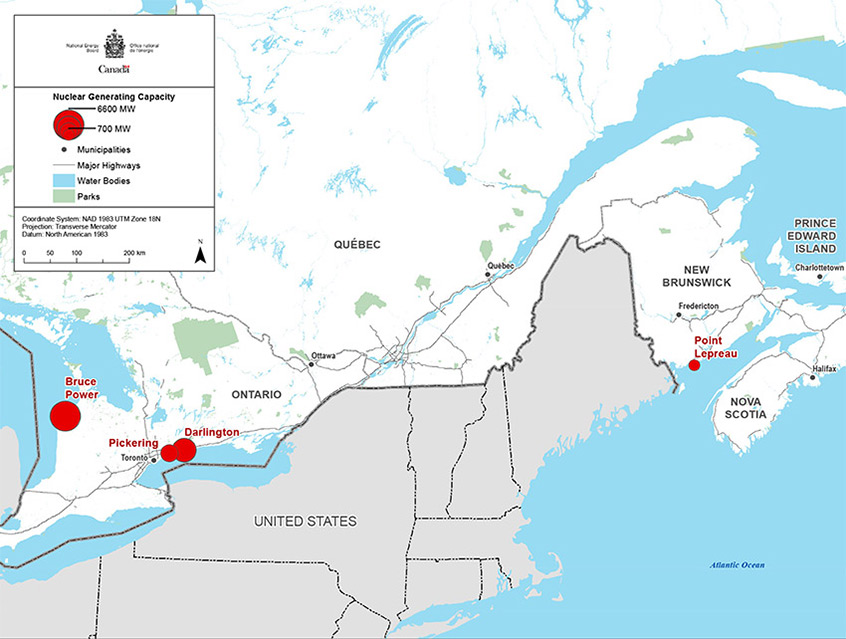

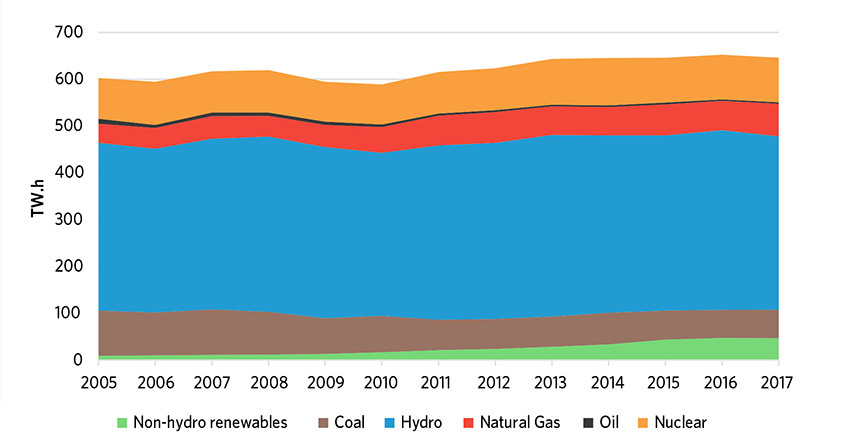

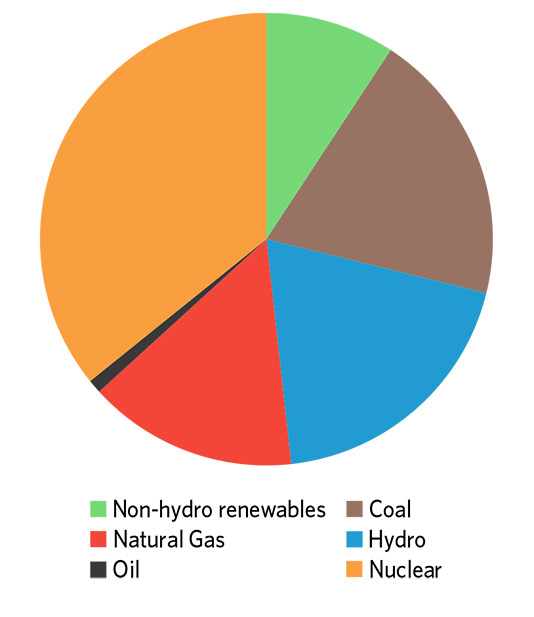

The mix of electricity generation sources in Canada varies significantly from province to province. The provincial mix is determined by a number of factors, including access to natural resources, historical infrastructure decisions, and policy initiatives implemented by provincial governments. Overall, Canada’s electricity is generated primarily by hydroelectricity (Figure 5).

In 2017, an estimated 57% of all electricity in Canada was generated using hydro. Nuclear was the second largest generation type in Canada, accounting for 15% of generation. All other forms of electricity generation, including natural gas, coal, oil, and renewables each accounted for 10% or less of generation.

Figure 5: Canada’s generation by source

Source: EF2017

The Cost of Generating Electricity

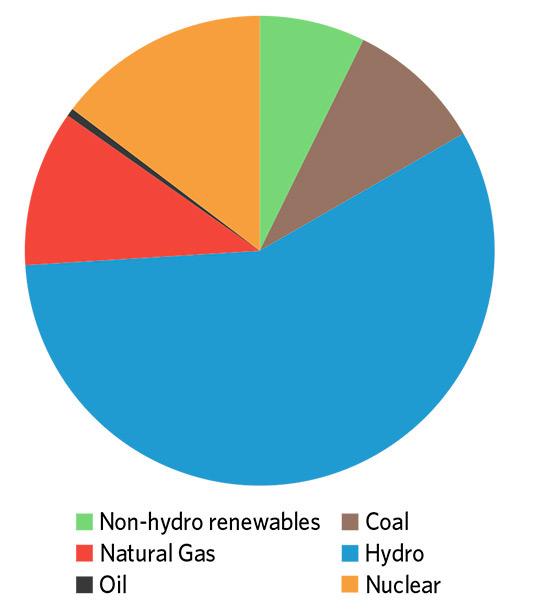

Figure 6: Range of levelized costs of electricity in Ontario

Source: Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO), 2016 IESO Ontario Planning Outlook

Generation facilities can have vastly different sizes, power outputs, efficiency levels, and other operational variables. Financially, the cost of initial investment, ongoing operations, maintenance, and fuel vary greatly.

One measure used to directly compare costs between technologies with such different characteristics is the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE). The LCOE is the price that a generator must receive over the life of a facility to breakeven. It takes into account all investments, operational costs and fuel costs over the life of the facility. It does not take into account the costs of decommissioning facilities. The values below have wide ranges, reflecting the costs of different facilities built over time.

Although LCOE allows for the direct comparison of technologies, it does have limitations. Values are highly dependent on projections, and do not consider non-financial factors, such as reliability and environmental costs.

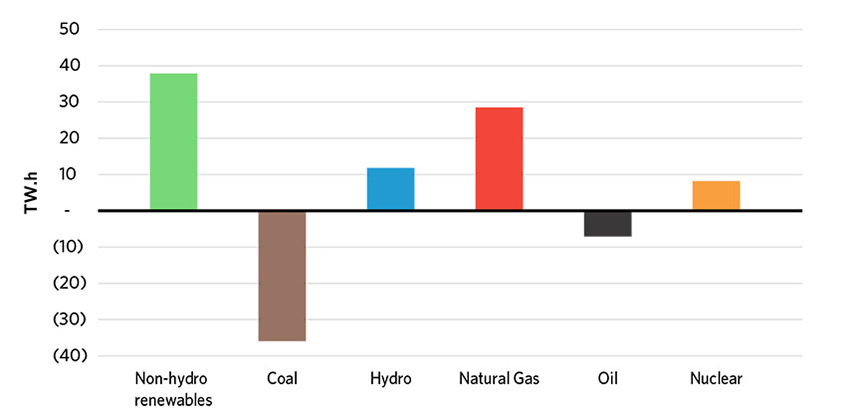

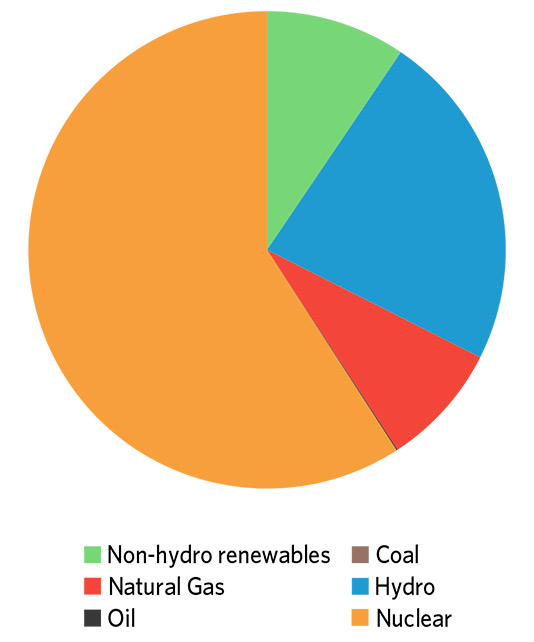

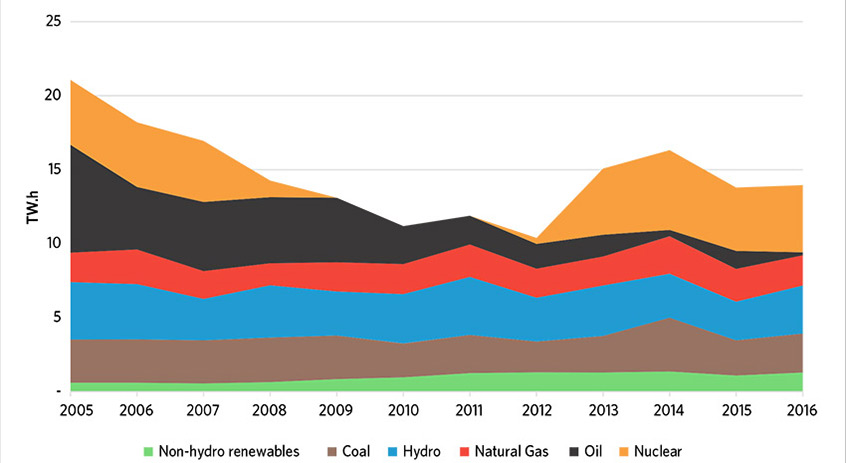

The generation mix in Canada (Figures 7 and 8) has shifted over the past decade as technology changed and investments were made in renewable energy. In total, electricity generation in Canada increased by 50 terawatt hours (TW.h) from 2005 to 2017. Coal and il generation decreased, while hydro, natural gas, non-hydro renewables and nuclear generation increased. Nuclear generation increased by 8 TW.h, or 9%, due to refurbishments at existing nuclear generating facilities.

Figure 7: Canada’s generation changes (2005-2017)

Source: EF2017

Figure 8: Generation in Canada (2005-2017)

Source: EF2017

Canada’s regulatory framework for nuclear energy

Canada’s nuclear industry is highly monitored and regulated. The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) is Canada's independent nuclear regulator. CNSC’s mandate is to:

- regulate the use of nuclear energy and materials to protect health, safety, and the environment;

- implement Canada’s international commitments on the peaceful use of nuclear energy; and

- disseminate objective scientific, technical and regulatory information to the public.

CNSC takes a lifecycle approach to regulating nuclear power plants. It regulates all stages of each nuclear power plant in Canada, from the environmental assessment required before plant construction, to the decommissioning and long-term waste management of the facility once operations are ended.

Canada’s provinces and territories also have a role in the regulation of nuclear energy generation. Provincial and territorial governments are responsible for electricity policy and legislation and, through public utility boards and commissions, for regulating electricity generation facilities; including some aspects of nuclear facilities.

For more information on the regulation of nuclear energy in Canada and other key government departments that play a role in the nuclear energy, visit Natural Resources Canada.

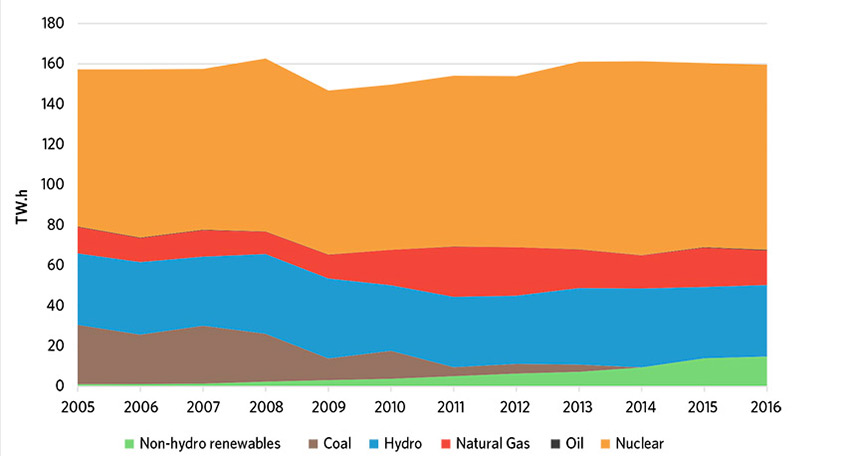

Ontario

Ontario has approximately 13 500 MWFootnote 1 of installed nuclear capacity. Ontario relies on nuclear generation for baseload power generation. Nuclear is the largest source of power generation in the province, accounting for an estimated 58% of total electricity produced in Ontario in 2017 (Figure 9). From 2005 to 2017, nuclear generation increased from 78 TW.h to 90 TW.h due to refurbishments and improvements at existing nuclear facilities. (Figure 10) In 2014, the province successfully phased out the use of coal, which generated 19% of electricity in 2005. Coal, which contributed to baseload generation, has largely been replaced by nuclear and a combination of natural gas and non-hydro renewables.

Figure 9: Ontario generation by source

Source: EF2017

Figure 10: Generation in Ontario (2005-2017)

Source: EF2017

Three nuclear power plants operate in Ontario. Bruce Power, located in Kincardine, operates Bruce A and B Nuclear Generating Stations. They have eight reactors with an installed capacity of approximately 6 600 MW. Four of the reactors at Bruce A were shut down in the late 1990s. Two of the units were returned to service in 2003 and 2004, and the remaining two in 2012. Bruce Power has plans to refurbish six reactors between 2020 and 2033, which is intended to extend the life of the station beyond 2060.

Ontario Power Generation (OPG) operates the Darlington Nuclear Generating Station, located in Clarington, and the Pickering Nuclear Generating Station, located in Pickering. Darlington houses four reactors with an installed capacity of approximately 3 700 MW. In October 2016, OPG started refurbishing all four reactors, which is scheduled for completion in 2026. Pickering houses six operating reactors, with an installed capacity of approximately 3 100 MW, and two reactors which have been permanently shut down. OPG plans to operate Pickering until 2024.

Ontario currently has no plans to add additional nuclear capacity to the energy mix. In 2013, the province deferred the construction of two new nuclear generating units planned for Darlington, due to low electricity demand growth in the province. Ontario released its 2017 Long Term Energy Plan in October 2017. In it, the Government of Ontario recommitted to moving forward with the refurbishment plans for Bruce and Darlington and the shutdown of Pickering.

New Brunswick

New Brunswick has 705 MW of installed nuclear capacity. Nuclear generation is the largest source of power generation in the province. In 2017, nuclear generation is estimated to have produced 39% of the electricity in New Brunswick (Figure 1). Like Ontario, New Brunswick relies on nuclear generation to provide baseload electricity.

Figure 11: New Brunswick generation by source

Source: EF2017

Figure 12: Generation in New Brunswick (2005-2017)

Source: EF2017

The Point Lepreau Generating Station is the only nuclear power plant in the province. It is operated by New Brunswick Power and houses one nuclear reactor. Point Lepreau was shut down in 2008 for refurbishment and returned to service in November 2012. It is expected to be operational until about 2039. During Point Lepreau’s refurbishment, New Brunswick relied on electricity imports to meet demand (Figure 12).

Other Canadian Provinces

Other provinces in Canada have considered nuclear generation over the years, but for a variety of reasons, have not added it to the mix. Nuclear is best used as baseload generation, and some provinces, such as British Columbia and Manitoba, have access to sufficient hydro generation to meet baseload demand. Other provinces, such Prince Edward Island, and the Territories, do not have the population size to support large scale nuclear generating facilities. In addition, construction costs and political choices to avoid nuclear, in some regions, have limited its use in Canada.

Quebec is the only other province to have used nuclear as part of its generating mix. Gentilly-2, owned by Hydro Québec, housed one reactor with a capacity of 675 MW. Gentilly-2, which was reaching the end of its service life, had initially been scheduled for refurbishment. However, in 2012, the Quebec government announced that the plant would be permanently shut down. Power in Quebec is produced predominantly through hydro generation and nuclear generation played a small role in the province. From 2005 to 2012, the last year in which Gentilly-2 was operational, nuclear generation accounted for 2% of total generation.

Hydro generated 90% of the electricity in British Columbia in 2016. In 2002, the Government of British Columbia launched a vision for the province’s energy plan, which included a commitment to not use nuclear power. This commitment is included in the province’s Clean Energy Act, which includes achieving “British Columbia’s energy objectives without the use of nuclear power”. In 2016, 97% of Manitoba’s and 95% of Newfoundland and Labrador’s electricity was generated using hydro. Both provinces have more than enough hydro capacity to meet demand in the province and are net exporters of electricity.

In Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Nova Scotia, power is primarily generated through coal and natural gas. Nuclear generation has been considered in all three provinces, but has not been developed and none of the provinces have plans to build any nuclear facilities.

In Alberta, where power generation is privatized, the government last commented publically on nuclear generation in 2009. At the time, the government commissioned a study of nuclear power generation in Alberta. After its publication, the Alberta government stated that it would consider nuclear power plants on a case-by-case basis and that no government resources would be spent on developing nuclear energy.

Saskatchewan has been considering the feasibility of nuclear for over 40 years. Today’s nuclear plants are too large for the province power grid, however SMRs may have potential to work in the province in the future. Research into SMRs is underway. However, the technology is emerging and not currently available as an option for use in Canada.

In Nova Scotia, a study was conducted in 2012 as part of the application for construction of the Maritime Link that examined various options for power generation in the province. The study concluded that given technology at the time, nuclear power generation was not economically feasible in Nova Scotia. In addition, The Nova Scotia Power Privatization Act prohibits the construction of nuclear power plants.

Prince Edward Island and the Territories have the smallest populations in Canada and do not have the demand to support a nuclear power plant. They had a combined capacity of 702 MW in 2016, just over half the capacity of the average nuclear reactor under construction globally in 2017.

- Date modified: